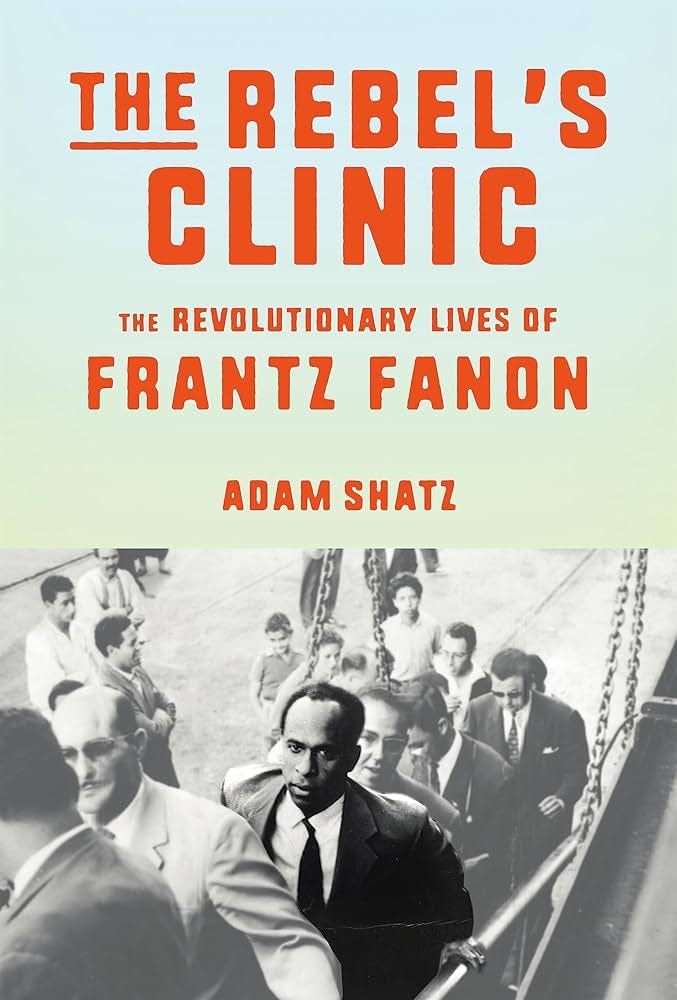

in january of the new year, i finished adam shatz’s thoughtful new biography of frantz fanon, THE REBEL’S CLINIC; a few days later, i had a violent argument with my parents about politics and lost faith in my own life.

before the fight, i had been quietly formulating some thoughts about the role of fantasy, representation, and ambiguity, as explored through both THE REBEL’S CLINIC and halina reijn’s new film babygirl. through these two works, i was thinking about how art and literature can make non-normative ways of life—otherwise rendered deviant, invisible, or implausible—more visible and therefore less unthinkable, in contrast to the oppressive social and political normativity i’ve become increasingly familiar with among upwardly mobile asian-americans, which often makes it harder to conceive of other lives, political movements, and non-normative values as viable and meaningful, if it thinks about them at all.

under this paradigm, there’s little to no value in resisting neoliberal politics, and little to no interest in doing so in the first place, given that these people are often rewarded materially and politically for their compliance. with this in mind, it is pretty refreshing to recognize a figure like frantz fanon, who didn’t waste time fretting about his complicity in colonialism or even a painful sympathy for colonized people, but in fact joined anticolonial resistance efforts and actively contributed to algerian independence and other decolonization efforts in africa.

in particular, i was struck by how fanon incorporated his ambivalence into his anticolonial efforts: while he recognized the psychic cost of violent resistance on freedom fighters and the failures and even crimes of anticolonial resistance movements, he nonetheless maintained his support of these efforts especially as a political official, noting that truth in wartime was whatever served the cause.

most centrists would decry this attitude as blinkered political fanaticism, but i was impressed by a firm commitment to a progressive politics. of course, bending the truth for political ends is not perfect—and, as shatz covered, the algerian national liberation front did commit many mistakes and even atrocities, from the philippeville massacre to the murder of fanon’s friend, abane ramdane—but conservatives and centrists too often weaponize conscientious objection to discredit progressive movements entirely, in favor of a tepid ambivalence that accomplishes nothing for those actually suffering. the world to come might still suck, but we should still try to make it happen—in freudian terms, to transform a neurotic unhappiness into an ordinary one.

as in public life, so in private life: films like babygirl argue that even conventional cis white women like romy mathis (nicole kidman) can transform their lives by pursuing unconventional sexual relationships, even if these relationships come in the form of otherwise conventional cultural scripts (ie, bang the hot intern). in my prospective essay, i imagined that i would explore why i thought a film like babygirl worked, despite my trepidation about the growing genre of mediocre Sex Thought Experiment art1.

problematically, most Sex Thought Experiments claim to be interesting because sex is interesting, transgressive, revelatory, irrational, etc, but they usually peter out at an ambivalence that turns out to be beholden to the same predictable conclusions that the works claim to challenge: problematic sex was either problematic all along, actually good, or an unknowable combination of the two. this last resolution (“it’s ambiguous…”) is theoretically interesting and complex, but in execution it nonetheless becomes obvious: just like in real life, we can’t make up our minds…2

on this spectrum of affirmation to indictment, babygirl lands more on pleasure than on problematizing or intellectualizing the dynamic. indeed, i’ve read some good criticism of the movie for its failure to grapple with the inherently predatory workplace power dynamics between romy mathis, a wealthy ceo, and her intern (samuel, harris dickinson), whom the movie generally presents as an uncompromised and equal agent in the relationship. in particular, in small wire, writer miriam gordis cites philosopher amia srinivasan’s THE RIGHT TO SEX to indict this rosy fantasy of mutual attraction. just as teacher-student relationships compromise the pedagogical transference of the classroom, gordis argues that boss-employee relationships cannot exist outside of the ethical considerations of work and the workplace:

Labor is an HR question in Babygirl. The problem with workplace violations is not their ethical basis but how hard it is to get away with them without being caught. … If there is a specificity to the desire to have sex with your employee, if it gratifies a certain kind of hierarchal urge and reproduces an existing labor relationship, Babygirl reduces it flatly to “kink.”

gordis makes a good point that the movie would be stronger had it actually considered the full ramifications of romy’s behavior in this movie and forced her to square real complications in her pursuit of sexual desire; it certainly would’ve led to a more complex and satisfying ending than the one the movie settles on. that being said, i think that the political ambivalence of this criticism overestimates the film’s project and its accomplishments. in the end, while babygirl doesn’t say anything progressive about workplace relationships (and hints at some unsavory consequences), i don’t really find that it says anything regressive about them either, mostly because i don’t think it says anything (meaningful) about workplace politics at all.

while babygirl neatly simplifies workplace ethics into hr formalities and even fetishizes the unequal power dynamic between samuel and romy, it doesn’t feel like a movie interested in money, class, or even power. rather, its interest in work exists largely in service of its interest in sexual desire, in that samuel’s intern position provides an easy narrative shortcut to the risk and transgression that turns romy on. i mean, i don’t think him much as an intern at all—he doesn’t really do any work? all the talk about hr, interns, and promotions provide the set dressing and narrative scaffolding through which two people from different generations and ways of life can encounter each other and enter into transformative dynamics of personal transformation and mutual recognition. of course, that does not exempt the film from class/labor analysis (and, in life, work does all of this too), but i just can’t imagine that any insights would form particularly meaningful conclusions about the world; no interns were harmed in the watching of this movie.

in that respect, babygirl reminded me of sally rooney’s novels and the Discourse around them: various critics have taken her books to task for how conventional they are—her relationships are too straight, not kinky; her characters are too thin; everything is too easy for them—but these arguments have never really felt relevant to me. yes, her works provide convenient fantasies of redemption through fulfilling platonic and romantic relationships, but those fantasies are still beautiful, meaningful, and honest.

for instance, when i read NORMAL PEOPLE, i don’t really care that the book presents marianne’s bdsm-adjacent preferences as evidence that she’s damaged (hence problematic political implications), because it doesn’t really seem relevant to me—the psychological acuity and elegant prose of that book convinces me that marianne is an interesting individual whose behavior reflects her specific background and interests (not universally), and i am moved by how she expresses and reconfigures her desires throughout the course of the novel towards her own happiness. this is not to say that NORMAL PEOPLE’s characters are not shaped by profoundly unjust political, social, and economic systems, but that in these novels, rooney is making a sustained argument for aesthetic and personal fulfillment even in the face of these characters’ own ambivalence, criticisms, and legitimate suffering; it is, as people love to say, kinda the point.

similarly, babygirl proposes a fantasy of meaningful female pleasure in non-normative sexual relationships outside of shame, repression, and rejection—and it works because the film genuinely kinda freaks it (?!). i know some other people have written about how the sex is not actually that hot in babygirl (this is usually my line of criticism for other Sex Thought Experiments), but i just don’t agree here? i think the first hotel room scene is fun and weird; i think the club scene is such a banger; i think harris dickinson dancing to “father figure” is Hot, actually. it’s still fair to criticize hollywood for its insistence on reading transgressive female sexuality only through submission3, but i still don’t think this film is all that conventional in that sense. for one, despite the film’s relatively tame depiction of pet play, this scene is not at all the conventional pornographic fantasy that romy mathis herself gets off to at the beginning of the movie. she really goes for it, with some very unflattering sounds!

in this scene and others, the film successfully draws upon the sensory pleasure of visual media as a voyeuristic conduit for the sexual pleasure that the characters are experiencing in this relationship. without getting into the basic film theory of the specific psychoanalytic identifications at play here: when i’m watching this movie, i get to share in some of the pleasure that the characters are experiencing themselves through the visual pleasure and the vicarious enjoyment of their sexualities. because the film successfully justifies and communicates the pleasure of this fantasy, it stakes a meaningful argument for pleasure over convention, for liberation over shame, for pursuing what you want at the cost of what might happen next. it makes an argument that it is good for a theater of mainly female audience members (as was the case when i saw the movie) to watch nicole kidman writhe on a cheap motel rug.

why care about things? why live? in the last two months, i’ve lost faith in my answers to these questions, let alone my ability to communicate these answers to another person. when it comes to the generative ai issue—whether we should continue to invest (or even just be excited about) large language model bots like chatgpt, bard, gemini—i thought i had prepared a solid set of explanations as to not only my personal distaste for the technology, but the broader political case against it: the costs of forgoing pleasurable activities like writing and art, the shitty, hallucinatory, and obviously inaccurate outputs of current ai models, the exploitation of both the underpaid workers who train the models and the creatives whose work they steal, and most of all the environmental devastation of generative ai’s carbon footprint and exorbitant water usage—but it occurs to me that none of those are deterrents if you simply… don’t care.

recently i was thinking about the massive population of people i know who just lurk, specifically on tiktok, reddit, and twitter. this form of engagement strikes me as starkly different from how people, or at least i, used to engage with these platforms in the early to mid 2010s: when i first joined facebook, instagram, tumblr, twitter, even google plus, i wanted to connect with people i knew and post cringey opinions on the internet.

now, most of the people i know irl have accounts on these platforms only for entertainment. they like to scroll through their curated for-you feeds and stay up to date on entertaining cultural trends (west elm caleb, luigi mangione, derek guy posts, etc), but they would never post anything themselves—often not even reposting to their completely blank profiles. for these people, social media has come to resemble a streaming service whose content production requires even less effort than the algorithmic slop of the Typical Netflix Movie. open twitter, scroll through tiktok, browse reddit; see what other people are doing.

of course, there are costs to this approach to engagement—not the least to creators themselves. it’s worth noting that this passive approach doesn’t necessarily divest people of psychic investment; whereas people used to care about posts because they knew the creators personally, they now invest this emotional energy into parasocial relationships with strangers that they don’t really know at all. and while it’s certainly possible to have real conversations on twitter, most people are more interested in the instant gratification you get from rubbernecking an ana mardoll4-esque scandal.

speaking from personal experience, twitter is a horseman in search of a head—hence the main characters; hence the ratioing, dogpiles, dunks; hence the endless discourse about age gaps, sex in media, “white women.” these conversations perpetuate a positive feedback loop: people fervently ratio someone’s dumb tweet into oblivion, which deters good creators from tweeting over the possibility that they’ll be ratioed over something that they didn’t really think much about at all, and the subsequent absence only makes people more desperate for the next quick fix of discourse.

this unhealthy dynamic has become (more) obvious now that corporate greed and poor executive decisions have run these platforms into the ground; i.e, it turns out twitter is not a streaming service that inherently provides good content, but a platform that was fun because it hosted entertaining and interesting people that used to talk about entertaining and interesting shit on there. now that those creators have left, it has become increasingly clear that good-quality content doesn’t just exist as some brute and inevitable fact of nature; even the dumbest memes were made by individual creators.

and, without them, what are we left with? fucking grok? the best part of twitter was how it provided an accessible platform for people to share their work and discuss current events. now, when i scroll through my feed, the algorithm is desperate to recommend me new content that i haven’t seen yet: low-effort compilation accounts that steal content from reddit and tumblr, viral tweets plagiarized word-for-word from other creators, recycled discourse from the last five years, and random tweets posted three minutes ago by people i don’t know (wow, the novelty).

this stupid slurry of low-grade content—which has not yet fully degraded into ai slop, fortunately—has made me realize every morning that, in my post-alarm routine of checking twitter, i’m really just subjecting myself to a dull chase of diminishing experiences in some sick attempt at feeling happiness5. that being said, there must still be plenty of users who enjoy lurking on the platform and enjoying these low-effort memes and manufactured drama. to which i want to say: you really have nothing better to do with your time?

to be fair, i’m sure that many of these people do not have twitter addictions as severe as mine, in which case using twitter mostly serves as a mildly diverting 15-minute experience every week. but i know that’s not the case for everyone—not the least the people who rack up hours and hours on tiktok every day. i’m not on tiktok myself, but i can’t imagine much first-degree social interaction on that platform beyond sending your friends funny clips to react to, which is not really a substantive dialogue so much as it is small talk—like, yeah, it’s fine to do this, but it usually sucks when that’s all you do. no, the social aspect of tiktok is mostly the digital conversation that it immerses you in, where you can engage with digital creators that you wouldn’t otherwise meet and stay up to date on the newest trends in culture—a landscape that many people participate in as pure consumers.

besides, even if you only watch one hour of tiktok every day, that’s not nothing, both in the literal time that you spent on that activity and the psychic consequences of these habits. speaking again from personal experience, my life has been shaped so fundamentally by new inventions the tech company has thrust in front of me. the worst, twitter, has reshaped my politics and personal beliefs to match the Left Twitter Party Line and conventional notions of what’s problematic—even when those criticisms are obviously made in bad faith6, and is honestly a huge part of youth left movements, organizing, and cultural politics.

meanwhile, streaming services like spotify have made art increasingly accessible to the average consumer, but increasingly vulnerable to the coercive forces of both algorithmic demands and shrinking economic margins. even if we disregard these platforms’ financial influence on the production and distribution of the music itself, they’ve definitely shaped my approach to art, where, as a spotify user (for example), i find myself constantly returning to the same playlists that either spotify made for me or that i made but spotify features on my front page, which causes me to repeat the same songs at the expense of discovering new music through organic recommendations or delving into individual creators and their backlogs (and eventually running my favorites into the ground7)8.

even relying on my car—my stupid tech car!—has irrevocably shaped my behavior on the road: while it’s definitely alerted me to some stupid mistakes that otherwise might have become accidents, it’s also made me a more distracted and less attentive driver, as the rearview camera means i don’t look over my shoulder anymore when backing up, i’ve come to rely on the car beeping near incoming obstacles as opposed to perceiving the closeness myself, and, if i’m tired or nervous or otherwise distracted, i use auto-driving mechanisms to just let the car park for me or even drive me to my destination.

of course, i’m not saying that all of these interactions are inherently evil, nor that i don’t benefit from these technologies—i do. but we ought to be cognizant of how these benefits always come at the cost of something else and accept them consciously, if we are to accept them at all. proponents of the tech industry (or a particular company) will often claim that you would unconditionally benefit from using their product(s)—it will make your life easier and more convenient by automatically completing work that you would have otherwise had to manually do yourself and making other tools more accessible to you. in other words, all you are sacrificing is your own inconvenience. and therefore you’re not really paying for anything at all—at most, you’re giving up suffering.

but even if all we are giving up is suffering, then we might as well choose to give up that suffering, instead of eagerly transferring all of our assets and our free will without thinking about it twice. after all, whatever happened to the basic bro truism “no pain, no gain”? it’s not always the case that you’re rewarded for your suffering, but sometimes you are! sometimes, you should gladly sacrifice your suffering for better conditions (material, political, psychic, etc); sometimes the suffering is a reward.

here’s a confession: sometimes, i let my car drive itself not because i need to, but just because i want to look at my phone—because i want to text and drive! and i’m not saying that the car inculcated this desire in me, but that the tech industry profits off of my short attention span and this convenient impulse to sacrifice meaningful skills for momentary entertainment, and it actually cultivates this attitude in its consumers. the more passive people want to be in their own lives, the more the tech industry—and capitalism writ large—can sell them solutions to minor problems. don’t want to leave your house? order doordash. want to watch movies on your couch? open netflix. don’t want to venture out to a bar? download tinder. every new feature is designed to keep you on the app(s) longer: customized feeds, controversy-driven algorithms, a barrage of push notifications…

to this, techies often like to respond with an ostensible concession: of course, like you said, not all suffering is made equal—so the tech industry must distinguish between meaningful suffering and non-meaningful suffering that otherwise can be eliminated (the classic “we invented the washing machine to liberate housewives” argument of a pro-industrialization advocate). companies that actually address users’ pain points will be successful and profit from their popular products; other useless ones will naturally die off when people no longer find them useful or relevant.

but this moral argument is completely at odds with these companies’ actual profit models and business practices; it’s the equivalent of arguing that the free hand of the market will provide for the people. even if successful companies have actually done good—if doordash has genuinely improved people’s lives by delivering food to their door or that facebook has revolutionized social wellbeing by allowing you to stalk your former high school classmates at 3am—these companies are equally happy to supplant their useful products with shitty ones, even when those shittier products turn out to be hugely unprofitable9. this is a basic “capitalism bad” argument that has grown more and more undeniable: as we can see with the latest billionaires x trump collab drops, silicon valley is not inherently beholden to democratic practices or to liberal values!

moreover, even if you unequivocally benefit from these conveniences, they nonetheless come at the expense of someone else’s time, energy, and labor. it is harder for independent musicians to make a living off of their art when spotify emphasizes—and underpays them for—ghost tracks that they wrote10. gig economy apps like doordash and uber exploit vulnerable workers, steal their money (literally), and offer the superficial freedom of working how you want in lieu of actual worker protections, like healthcare and workers comp. meanwhile, the new ai craze is built on the backs of vastly underpaid workers who reviewed violent and traumatic material (chatgpt)—and is exacerbating the climate crisis that has most immediately threatened those already made vulnerable to disaster by poverty and colonialism.11

these failures are not just the tech industry betraying its initial promises or falling victim to its own hypocrisies; they speak to the fundamental ethos of these companies, which is to make as much money as you can, doing as little as possible. as with product, so with company: these incidents are symptomatic of the exploitative and lazy nihilism that profits off of servicing your dependence. and i feel insane when i have to advocate why we should care for the meek, the poor, and the vulnerable; this is literally basic christian doctrine. is that any way to treat human beings? to treat you?

a conservative accusation that has often been leveraged against me12—and that i do take seriously—is that leftists like me do not care about real people, but only about a certain alienated ethics of hypothetical suffering. according to these conservatives, i don’t really understand the experiences of those i’m advocating for and therefore don’t really understand the systems and solutions that would actually make a difference; i care more about the abstract moral value of an argument than its actual political implications and economic ramifications. it implies that this empathy is a selective choice: i’m kind to people i will never meet and unkind to those who actually provide for me and make the kinds of unsavory sacrifices that have made my current life possible. every form of privilege is easy to disparage until you have to give it up.

and i don’t disagree, not completely; even though i think it will always be good to care about other people (as opposed to not caring about them), i do think that my leftism is generally pretty unbaked. that being said, that’s not because leftism itself is inherently flawed, but that i’ve gotten my politics from twitter—and that these problems once again go back to how the tech industry has corroded modern life.

politically, despite the overt leftist content that i’ve already cited, these platforms generally cultivate a conservative mindset: close-minded, paranoid, and individualistic13. you learn about the world without learning about where the information comes from; you’re primed to accept misinformation and uncritical interpretations of the world insofar as it reinforces your own perspective. that’s how you get white women advertising insane safety gadgets to prevent you from getting kidnapped in the target parking lot, or why conservative parents are sincerely alarmed about an imaginary spike in kids identifying as cats or whatever—the more time you spend on these platforms, learning about imaginary ways of life, the less time you spend defining your own.

in the end, the mediating factor of technology has alienated me from my own experiences. your only life is one that you’re not directly experiencing, that you’ve outsourced to various apps to optimize for you. there is, for example, a real pleasure to driving a car—which you don’t experience if you just ask the car to do it for you, if you see driving as merely a means to get from point A to point B. even if you hate driving, even if you think road safety is just that much more important, you have to recognize that you’re giving your own subjective pleasure up—you’re forgoing an experience that you might otherwise have had.

at its worst (most of the time), the tech industry strives to replace every inconvenient means with its corresponding ends; it offers to do all the work that you don’t want to do so that you can just get what you want. you don’t even have to do something with what you’ve got—if you wanted easy access to music to make playlists, well, spotify will make those for you; if you wanted to borrow a book to learn more about fanon, ai will summarize that for you; everything you could do is simply an opportunity for you to not do it. a life of all ends, though, is a very depressing life indeed—a life where you don’t really have to do anything at all.

in any case, this alienation has made it easier for people to simply not care about the costs of their technological habits and the people that these companies exploit. while the popular “no ethical consumption under capitalism” slogan ought to empower people to pick and choose their political battles (at worst)—it more often justifies their resignation to the anti-intellectual and misanthropic proposition that most suffering is okay insofar because it’ll happen anyways. the internet has displaced those harmed by this consumption to another room. you can’t recognize them if you keep scrolling; even if you do, they’re functionally not real to you. what’s the alternative—you feel really bad? what, are you depressed?

well, yes: either way, you’re depressed. in fact, the conservativism of the tech industry would like to make life depression and depression life; it would like to portray people who recognize real instances of exploitation as sad and miserable and delusionally preoccupied with hypothetical struggles, and it would like to encourage other people to pay for meaningless lives where you don’t care about other people and you don’t need to do anything at all.

most people would claim that tiktok provides free entertainment and is generally a nice-to-have, but i don’t think that’s true. i think there’s something i am giving up by spending so much time on twitter, by relying on my car to park for me, on using my photos app to remember what i was doing last year. the most optimal life is one in which you get whatever you want and sacrifice nothing in the process: not your time, not your energy, not your vulnerability or your class interests. tech companies claim that their optimizations will reduce all the useless busywork of your life and free your time up—for what? for scrolling through twitter? for watching digital ads? for making these very companies more and more money? for you to do even less with your life?

depression without suffering; what a project. everyone is writing about this these days: every piece i read, from emily st james to john ganz. we are living a pointless life at the expense of others. we are exploiting people and destroying the future just for the paltry gains of an “optimal” life, which is to say: for nothing at all. it would be one thing if these sacrifices really produced a life worth living, but what are we selling our souls for? clinical depression? the prospect of going to work and then dying; the prospect of being right on the verge of losing your assets and becoming yet another invisible member of the precariat; the slim chance that you might be barely okay. to train ourselves into not caring; to give ourselves a form of voluntary depression.

when you gain convenience, you give up suffering; it follows that when you give up convenience, you gain suffering. and this is a productive path for people, i think, not the least so that you can assume this suffering now in the place of other more vulnerable subjects or even you, in the future, when you realize you have no psychic skills whatsoever. why are the children depressed? maybe because there is no point to doing anything meaningful if it can be done for you—usually at the hidden expense of someone else’s time and effort. listen—do you want to live? what do you want to do with your life?

with all this being said, does anyone care? like, do ai bros care that human art produces subjective meaning? do people want good tweets, or do they actually enjoy grok and meme compilation accounts on instagram that lazily screenshot viral tweets on twitter and tumblr?

this brings me back to the fanon biography. i cannot emphasize enough that i have not studied phenomenology14—everything i know is from shatz’s writing on fanon’s encounter with merleau-ponty’s THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF PERCEPTION and hegel’s PHENOMENOLOGY OF SPIRIT, neither of which i’ve read. from what i do understand: phenomenology is a school of thought that emphasizes the physical and psychic experiences of the body in philosophical theory, as opposed to more abstract and disembodied analyses of identity, free will, and freedom—the precursor to the modern politics of lived experience. for fanon, phenomenology helped him articulate his physical experiences of anti-black racism: how the white world interpreted, feared, and subjugated the black body and how black subjects bear the physical and psychic damage of racist politics and societies.

crucially, this form of knowledge is acquired from the body and its experiences. ultimately, there is a limit to my moral argument about technological dependence, which is the gap between your and my lived experience. writing is a project to bridge that gap; i can explain how i feel, and i can even explain how it’s rooted in philosophical and political analysis, but i can never really impose a love of beauty or joy or meaning on someone else. if you don’t care about your own autonomy, if you don’t care about human suffering, if you genuinely feel nothing when you see a beautiful sunset or have a lively conversation—then i can’t convince you otherwise.

again, this state mirrors clinical depression, in which meaning is not self-evident; one has lost their capacity to feel pleasure or joy or happiness, and is deprived of the existential reasons that make life otherwise worth living. in conservative social settings, political empathy often turns into a reductive circular debate: you’re sad because you care, you care because you’re sad. the ultimate fantasy becomes to not to care at all.

this is most obvious when it comes to the meaningless process of making art, which is meaningful precisely because we imbue art with meaning. good art expresses the complexities of political and psychic subjectivity and is about ambiguous aspects of human experiences, and, even outside of the edifying power of artistic engagement, it contains self-evident meaning that you should connect with just for itself. if you’re not making your own songs, are you even having fun? if you’re not writing your own works, what are you even learning? don’t you feel that knowledge is meaningful? that watching a well-written movie is fun?

obviously, i don’t mean to equate anticolonial resistance with bdsm with the plight of the terminally online, but to me they seem to be speaking to the same theme, even if at different decibels. just as fanon’s psychiatric assessments explored the undeniable experience of anti-black racism, babygirl roots its protagonist’s desires in her body. it’ll always matter why she feels this way, but more importantly—she just does.

and for all of their faults, these works show you a way out of your own ambivalence: by realizing that there are more important ways to live than to sit around in your own head, wondering what the most optimal path might be, hoping someone else will make those decisions for you. in their vulnerability, so many people remain stuck under this state of suspended childhood, but tiktok is not your mother; twitter is not your father. if i have to choose between THE REBEL CLINIC’s and babygirl’s and rooney’s fantasy of positive desire and the technology fantasy of negative experience, i am going for the former—at least it gives me something worth working towards.

there’s a tendency in right-wing thought to reduce “normative” ideas to abstract moral goods. oh, dei is a convenient cause that makes liberals feel good about themselves; trans inclusion is just to indulge a delusion and not make anyone feel bad; it’s nice to solve world hunger, but there’s no such thing as a free lunch. this way of thinking prioritizes rational decision-making over actual rationality; it’s a faux-intellectual mindset that actually peddles anti-intellectual assumptions that are not only reductive, but also precisely the kind of “conventional thinking” that these people claim to be challenging.

when conservatives posit that there is something fundamentally fake or disingenuous about left-wing ideology, at a certain point, i just can’t prove it any further. the collective good is not an abstract argument, and subjectivity is not some frivolous experience; you can’t be told that your life does not matter, that your happiness is besides the point, that someone else knows what you should want, without suffering some serious psychic damage. maybe you’ll displace it on someone else, but i honestly think it’ll come back for you at some point, and you’re going to have to do something about it. and, if it doesn’t, it should.

shouldn’t you know this? haven’t you experienced it yourself?

one problem of modern phenomenology: if the last decade of leftist politics has broadly emphasized lived experience, then the internet has weakened—if not destroyed—many people’s connections to the lived world and thus discredited their abilities to claim political struggles as their own (the plight of the terminally online). it’s like when you hear a nepo baby start talking about the difficulties of making their own way in the world—like, you don’t know the world, you know a specific and optimized version of the world. and you won’t get many valuable insights from an optimal life; you can’t learn from the negation of experience.

as i was observing to someone the other day: as someone born in 2000, i probably just missed the ai education wave. when i was in school, no one was using chatgpt to write their homework assignments or take their remote tests—the technology just didn’t exist—but now i hear about it all the time from students and professors alike. and as a young person who was recently very vulnerable to the pressure placed by overbearing parents, the social implications of prestigious grades, and an increasingly shit job market, there is a nonzero possibility that i might’ve capitulated to a technology that could have given me an extra edge and made my stressful life a little easier. i can easily imagine a version of myself who claims to be sacrificing very little by using ai. what are you giving up anyways? it’s not a big deal. it’s worth it.

the problem is that these interactions create a self-reinforcing feedback loop: modern technology is designed to reconfigure your behavior and your interests even before you know it, especially when reinforced by a capitalist system that rewards this kind of relationship. an easy example is just the smartphone—it is so easy to use your phone at a moment’s notice, and it is so hard to not use your phone when everyone else uses their devices to interact with each other and occupy themselves. i find myself reaching for it reflexively whenever i’m even just a little bored.

coming back to the school example: you can’t always trust people in vulnerable places to make the best decisions for themselves, not when there seems to be no material or social incentive to doing so. there was a tweet that went viral lately where someone was like “is there any reason to be a good person?” people were dunking in the quote tweets, but i think it’s honestly a reasonable question that speaks to basic existential questions about human happiness (the social reaction is justified though).

part of my recent literary analysis has focused on politics as a means of informing your desires against your own will (à la judith butler’s assertion that gender is a sociopolitical negotiation in which norms work upon you and are thus incorporated into your actions). as a depressed subject of silicon valley capitalism, morality may not actually be self-evident and obvious. what if you don’t know what you really want? what if you’ve only experienced a limited slice of the world that has produced similarly narrow desires?

in her existentialist philosophy, simone de beauvoir defines freedom as the highest existential good, but crucially she clarifies that freedom is not the freedom to oppress others—the slaveholder cannot claim that he pursues his own freedom by oppressing the freedom of his slaves. likewise, it occurs to me that the supposed advancement of ai technology that proponents get so excited about is fundamentally a disingenuous one. you can’t say “let me be excited about the intellectual accomplishments in this new technology” about a technology that makes it harder for other people to get excited about intellectual accomplishments by supplanting the meaningful intellectual work that they would otherwise be doing. we cannot accept a technology that would make it harder to imagine better ways of life. we cannot imagine how to stop imagining. we should not imagine how to stop imagining for ourselves. that would make it harder for us to conceive of other forms of life.

when i say that tech makes people depressed, when i say that it is exploitative and makes it harder for good people to put out good work (namely, artists, whose work is meaningful and interesting and makes me happy), i’m not saying this to make you feel bad about nothing; i’m saying this to make you feel bad about what’s already bad in your life right now.

if you don’t believe me, that’s fine. you can sacrifice your soul to an apathetic future, but i’m not going to do that to mine.

see: ACTS OF SERVICE, LITTLE RABBIT, WE DO WHAT WE DO IN THE DARK, THE ADULT, A GOOD HAPPY GIRL, EVERYTHING’S FINE, etc.

if you don’t know who this is, good! your brain looks luminous and healthy.

matthew weiner amc cast me as a modern day don draper…

a recurring act in my life: me messaging someone that “oh good x discourse was making me feel insane” upon seeing a tweet that finally articulates the contrary opinion. messed up mind…

rip good luck babe, i can’t listen to you anymore…

ai advocates like to claim that they’re taking the problems of ai very seriously—that is, the problem of the ai singularity, or of roko’s basilisk. to which i have to say: are you fucking serious? above all, these cynical fears of sentient technology only serve to diminish all other costs—they’re not as important as the ai singularity. if we fix the ai singularity, we don’t have to care about these problems of worker exploitation or ecological damage or the fact that these products don’t fucking matter…

most recently by the conservative christians of THE HEROES OF THE FOURTH TURNING, THE BROTHERS KARAMAZOV, and my very own parents :)

i genuinely can’t even say it out loud without stumbling over the syllables.